Article available also in PDF

10 minutes read time

2021 just started and we are working and learning from home via online platforms as often as we can, we experience culture online, we order things online delivered to parcel machines and we talk to family and loved ones on Messenger and Skype. Let us go back in time to the cholera outbreak in the 19th century. Were there any special mail handling procedures at that time?

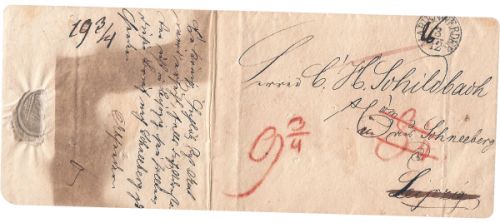

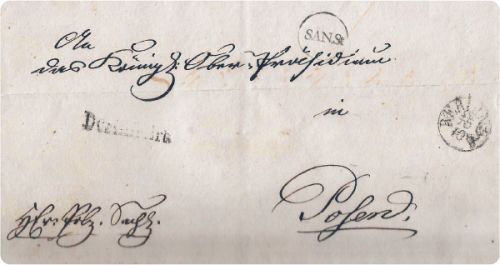

Justyna Jeleniewska-Janusz: During the outbreak, the mail was still being delivered, but all the letters were disinfected – you can see that on the two letters showcased in the Museum of Post and Telecommunication in Wrocław. One of them was pricked with needles and fumigated (Kwidzyń – Leipzig from 1821), the other has the stamps saying “Dezinfekirt” and “SAN. St” – sanitary station (Berlin – Poznań from 1831).

And what would our conversation look like 100 years ago in normal circumstances, assuming we were in two different cities?

Tomasz Suma: We would have two choices – either write a letter or call.

We would use unusual paper and make sure that our handwriting is legible. We would dip our pen tip in an inkwell, being careful not to soil the stationery, but being proficient in letter writing would not allow us to make such a mistake. Of course, this letter would also need to be posted, so we would have to go to a nearby post office. We would put it in an envelope purchased there – an ordinary one without any special markings – and affix a postage stamp paid for in Polish marks. Depending on the month of the year, we would choose a purple postage stamp with the value of 3 Polish marks (mk) designed by an outstanding graphic artist Edmund Bartłomiejczyk, issued in January; at the beginning of March we could get a stamp with a surcharge for the Polish Red Cross also designed by Bartłomiejczyk with the value of 6 or 10 mk, with a 30 mk surcharge for the Polish Red Cross; at the end of March you would get the 10 mk “Sower” stamp designed by B. Wiśniewski; in May you would buy “Enacting the Constitution” by E. Bartłomiejczyk and in June “The Eagle on a Baroque Shield” designed by E. Trojanowski. All these stamps, their varieties, variations and original designs, as well as an interesting collection of pens, inkwells and stationery can be found today in the Museum of Post and Telecommunication in Wrocław.

correspondence Berlin Poznań, 1831

correspondence Berlin Poznań, 1831

The other way to talk would be a phone call – sometimes more than one. Provided, of course, that both of us were lucky enough to be among the 50,000 phone service subscribers at the time. In the first years of the Second Polish Republic, the telephone was no longer an exotic technical novelty, but still an indicator of social status. In other words, if a century ago we belonged to the group of citizens of the Interwar Poland, who could afford the luxury of having their own telephone at home, our devices – manufactured in Poland by the Swedish Ericsson – would certainly hang or stand (depending on the type) in an honorary place in the hallway. Not because it would be a quiet place to talk, but because this was where a visitor would see the phone first upon entering our homes. It was still something to brag about at the time.

In most cities, telephones were installed in government offices, post offices, sometimes in public call rooms. However, we could only dream of a private phone – insufficient telephone network coverage, expensive calls and subscription fees discouraged people from getting their own phones. If you were in Warsaw, you would have the worst chances of getting a phone at home (10%), since there were only 5,000 phones in use there – only one phone for nearly two hundred residents. A similar situation was in Bydgoszcz (18%). You would get a better chance in the Greater Poland region (24%), then in Lesser Poland and in the city of Cracow (up to 37%). What is more, this would come at a cost – in the late 1920s and the early 1930s, a ten-minute phone call would cost us the equivalent of roughly 300 PLN, or 70 euro. Thus, phones were often found only in the homes of wealthy urban families and in state administration. A normal Pole could call from a public call room – if they had anybody to call and if there was such a facility in their city.

I did not ask about two cities by accident – the Museum of Post and Telecommunication was established 100 years ago – on 25th of January 1921 to be more precise – in Warsaw. Why was the museum moved to Wrocław and how did it happen that it is the only facility in Poland that holds collections related to the past of the Polish post?

TS: The museum was indeed founded a hundred years ago in Warsaw, on the initiative of the ministry, or rather as one man’s personal project. It was Władysław Stesłowicz, Minister of Postal Services and Telegraphs in 1920–1922, who spared no time, effort and commitment to make the institution an important and visible place on the cultural map of the capital and the whole of independent Poland. According to his concept, the Polish post museum was supposed to be a monument built by the Ministry of Postal Services and Telegraphs to commemorate Polish independence. The awareness of the need to preserve the history of the Polish postal services and its people in the collective memory caused a continuous influx of donations and messages containing memorabilia which confirmed the extraordinary history of the Polish postal service and showed how it developed and operated in the contemporaneous times. This concept was then undertaken by his successors before and after the war. There was also no need to create a competing museum, nobody thought about that in these terms. Since one museum was already operating, it was deemed the only place for preserving the national heritage and history concerning this area – at least that was what people were thinking at that time. The Museum survived in Warsaw until 1951, when the state authorities made a decision to shut it down, along with all the other technical museums that existed at that time (Museum of Industry and Agriculture in Warsaw, Industrial Museum in Krakow, Museum of Agricultural Technology in Szreniawa and Museum of Post and Telecommunication in Warsaw), as well as the Union of Polish Museums.

The idea of reopening the museum was revived at the beginning of 1954 at the ministerial level – at that time, there were already talks about moving it to a different city. As a result, there was the suggestion to establish a new museum in the Recovered Territories, with Wrocław being proposed to be designated as the new seat of the Museum. It was certainly a place that had to be nurtured more than any other region that experienced the war – after all, the authorities had to prove their centuries-long Polish history at all cost. This was the only case where Warsaw capital voluntarily gave up its museum to benefit another region.

correspondence Kwidzyń – Lipsk, 1821

correspondence Kwidzyń – Lipsk, 1821

Why Wrocław? Why not another city in the Recovered Territories or in Pomerania or the former East Prussia?

TS: What probably (or rather definitely) led to that decision was Władysław Kostro, a high-ranking political, trade union and postal activist, who worked in Wrocław and Warsaw. He had the ability to persuade others to follow his concepts and ideas. As they say – the right man at the right time in the right place (laughs). He suggested Wrocław, which was generally associated with the Recovered Territories; he convinced the ministry that it was a brilliant idea, that after the 1948 Exhibition of the Recovered Territories and the 1952 Congress of the Recovered Territories – both of which were held in Wrocław – it would be the third most important event highlighting the identity of these regions. And… it worked. Two years later, a new museum was officially opened in the capital of Lower Silesia and the largest city in the Recovered Territories.

The museum’s iconic exhibit is a 19th-century postal stagecoach. What other interesting objects can the museum offer when it reopens?

TS: We are in the process of preparing a new permanent exhibition in the Historical Hall, where the visitors will see exhibits which have never been shown before, including the oldest surviving original Polish postal signboard from the 18th century from Słonim, as well as an 18th century stamp from this post office. We will also showcase a notebook from the Polish Legions’ Post Office with the original signatures of Piłsudski and the legionnaires of the First Brigade, a letter from Emperor Franz Joseph in recognition of the excellent work of Polish postmen under Austrian rule and the only surviving Polish copy of the uniform of a ministerial postal official in the Kingdom of Poland.

JJ-J: Collectors will certainly be enthralled by the first Polish stamp called Poland 1 from 1860–1865 and the 400th Anniversary of the Polish Post from 1958 printed on silk in the steel engraving technique.

Monika Orzech-Myrlak: The Museum of Post and Telecommunication in Wrocław offers more than just postage stamps – it also holds telephones, telegraphs and television sets. Among them, one of the most interesting objects is the Hughes telegraph from 1918–1939, with a 28-key keyboard, which stored information on a paper ribbon in the form of numbers and letters. One can see a strong inspiration with the piano – the inventor’s favourite musical instrument. Other rare objects include numerous antique wooden wall-mounted phones from the 19th century – quite a treat for the builder and lover of antique telecommunications exhibits. However, the most interesting among them are telegraphs, and we definitely have no shortage of those – including the one from 1914, operated by the Reichs-Telegraphenverwaltung, characterised by its simplicity and reliability.

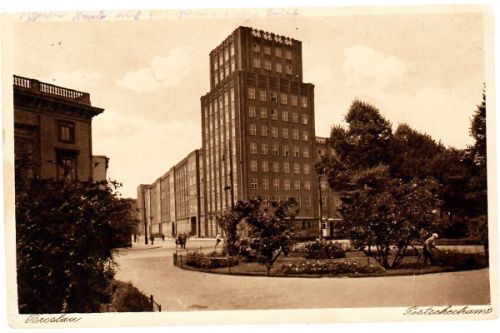

Building of Poczta Główna, ul. Krasińskiego before 1930 r., ph. from archives MPiT

Although the building at Krasińskiego 1, which houses the Museum, is not currently open to the public, let us stop there for a moment. Its construction in the 1920s was quite a big deal at the time – some said that it was the only skyscraper east of Berlin. What was it built for and is it true that in communist Poland the authorities used its tower to jam Radio Free Europe?

JJ-J: Indeed, it is true. During the communist era, until 1953, the authorities installed devices used for jamming the signal of the American government radio station due to the fact that in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, the free flow of information was banned by the governments. The building was particularly conducive to that purpose – it was one of the first two skyscrapers in Wrocław, with a 43-metre-tall brick tower with a reinforced concrete inner structure. This characteristically long and narrow building was designed in 1926 by Lothar Neumann, an architect who studied in Breslau, Danzig and Munich. It originally housed a check office – a type of bank, which held people’s savings.

These days, one may encounter meet a bike courier far more often than a postman, and the urban landscape is dotted with parcel machines – back in the day, there were phone booths. What was the situation like in Wrocław in the first years after the war, when the city was being rebuilt and the communication with other cities was re-established?

MO-M: The situation in post-war Wrocław was particularly difficult, but after 1945 there was a massive resettlement movement and the residents started to clean up the ruins and destruction. They had one goal in mind – rebuild Wrocław and restore it to its former glory. Streets were cleaned up, new buildings were erected and bridges were overhauled – all so that Wrocław could develop its transport and communication infrastructure. “The Polish Post, Telegraph and Telephone” contributed greatly to the rebuilding of the city. When Wrocław was still in ruins, the first post office was opened in Trzebnica, then in Legnica. On 16th of May 1945, the first post office in Wrocław was opened on Marsz. J. Stalina Street (currently Jedności Narodowej Street). It was a beginning and a glimmer of hope for the development of postal services. It allowed people to send letters to families living in the distant Borderlands, get in touch with their loved ones, and sharing their lives in post-war Wrocław. At the beginning, telegrams could be sent only to Germany – to authorities and offices, but in the same year new post offices were opened in Leśnica, Różanka, Karłowice and Sępolno.

On 15 August another post office was opened in Wrocław, named Wrocław 2, located on Małachowskiego Street. The new office enabled residents to send packages up to 20 kilograms. The real revolution came when the postal services offered postal orders of up to 2,000 PLN, as well as PKO bearer cheques. “Polish Post, Telegraph and Telephone” then went on a hiring spree. It all grew at a very quick pace – in 1946, there were 35 mailboxes and by 1948 there were 85. The lack of the actual mailboxes somewhat hindered the growth, so the workers repainted old German boxes from blue to red and painted the Polish coat of arms on them.

On 25th of May 1947, the first telephone exchange was put into service in the Town Hall, which boasted 800 subscribers at the time. It was installed in the building of the Post and Cheque Office at Krasińskiego 1-9, which now houses the Museum of Post and Telecommunication in Wrocław. In 1947, there were already 414 postal and telecommunications outlets, 94 million letters and packages were sent, 5,166 people were employed, and 25,214 telephones were installed.

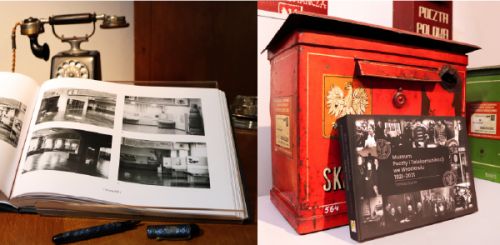

monogrpahy Museum of Post and Telecommunications in Wrocław 1921-2021 published for its 100th anniversary

monogrpahy Museum of Post and Telecommunications in Wrocław 1921-2021 published for its 100th anniversary

The current situation is hardly conducive to celebrations – especially the bigger ones that one would expect in the context of such round anniversaries. What plans does the Museum of Post and Telecommunications have for its 100th anniversary celebration?

MO-M: To our regret, we had to move the majority of our celebrations online, and we have also had to move the official part to June, when the COVID-19 outbreak hopefully calms down and we are able to once again open our doors to visitors… Even though we celebrated our 100th birthday on the 25th of January.

On YouTube, we are publishing a video series presenting 100 exhibits in detail, all with a commentary by the collection supervisor. Every month we will present the so-called Gallery of One Exhibit. That’s what we are going to do online. What about live events? In June, we are planning to officially reveal a postage stamp dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the Museum of Post and Telecommunication in Wrocław (with a print run of 200 stamps) combined with the publication of our catalogue – the first historical monograph describing the history of the museum, which contains previously unpublished archive materials. We are also going to mint a commemorative 0 euro banknote, which has been extremely popular among European collectors since 2015.

However, we also have a special thing in store – the presentations of works by two graphic artists and designers of postage stamps and banknotes: Czesław Słania and Andrzej Heidrich. If the pandemic prevents us from doing it live, we will showcase their works online.

Interviewer: Magdalena Klich-Kozłowska