Article also available in PDF

4 minutes read time

Made of clay

The very name of the estate – Huby – might sound quite intriguing. Before the war, the estate was called Huben, and earlier – before 1744 – it bore the name Lehmgruben, or “a clay mine” – and clay was indeed mined there using the open pit method. The empty pits were turned into fish ponds – the last pond in the area was filled up in the 1970s – it was exactly where you can now find a petrol station on Hubska Street. The German name – Huben – on the other hand, is the plural of the word “hube”, which stands for a hide of land – in the Middle Ages it was used as the basic unit of area. Given this knowledge, it should be easy for you to figure out where Gliniana Street in Glinianki came from, but what about Komandorska or Joannitów Streets [ang. Order of Saint John]? The village used to belong to the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, and its basic administrative unit was the so-called Commandery.

kamienica na skrzyżowaniu ulic Borowskiej i Glinianej; photo. archives of Wratislaviae Amici polska-org.pl

The genesis of Huby

By official resolution, the Huby district absorbed Glinianki in 2004. In spite of that decision, Glinianki came first – the first mentions of a village by this name can be found in 1346, and in 1868 it officially became a part of the city. The overpass along Pułaskiego Street was built a couple of years later, which means that before it came to be, the entire area was practically cut off from the rest of the city by the railway bank. Between 1808 – the date when the city officially crossed its medieval borders – and the end of the 19th century, the entire area stretching from Podwale to today’s Wiśniowa and Hallera Streets was built up with townhouses. Similar buildings went up along the northern embankments of the Odra River, in Przedmieście Oławskie in the eastern part of the city and in Przedmieście Mikołajskie in the west, but the scale of the so-called southern district was disproportionately larger. While Przedmieście Oławskie and Ołbin tend to feature poor tenement houses, the southern part of the city was far richer and more elegant – in addition to residential buildings, monumental seats of state institutions were erected there, including the Wrocław Railway Management Bureau located in Huby. To this day, you can read the memoirs and journals of people travelling to Breslau, who were in awe of the modern character and the grandeur of the entire establishment.

siedziba Dyrekcji Kolei; photo. Wiktoria Mróz

siedziba Dyrekcji Kolei; photo. Wiktoria Mróz

Post-war scars

During the siege of Breslau in 1945, the south side of the city became the scene of an epic battle between the Soviets attacking from the south and the defenders of Festung Breslau. The fierce fighting left its mark on the urban tissue – entire housing estates were turned into ruins, mainly in the western and southern parts of the city. Bullet and shrapnel holes can still be found in the walls of the houses, and the old buildings are often chaotically mixed with the construction of the communist era and the wild capitalism of the 1990s. Millions of cubic metres of debris were disposed of after the war – used to fill in former clay pits and sand pits, as well as to build hills, which were later covered with a layer of dirt and planted with trees. This is how the highest point of the estate – Andersa Hill – came to be. It might be worthwhile to climb it to take a look at the panorama of Huby, the water park and the tram depot in Gaj… or to use the pumptrack, which was built as a project implemented under the Wrocław Civic Budget.

ul. Gajowa, lata 70. XX w.; photo, archives of Wratislaviae Amici polska-org.pl

ul. Gajowa, lata 70. XX w.; photo, archives of Wratislaviae Amici polska-org.pl

Built to impress

There were several interesting public buildings in the estate, including the famous St. Elizabeth Middle School, previously located at the Church of St. Elizabeth, near the Market Square, later moved to an elegant building on today’s Dawida Street, which now houses the Institute of Psychology of the University of Wrocław. Nearby, you can find the monumental Wrocław Railway Management Bureau, which – mainly thanks to its impressive size – played the role of Gestapo headquarters in More Than Life at Stake. A bit further to the south-west, there was a beautiful neo-Gothic Evangelical Church of the Holiest Saviour (Salvatorkirche). Built in 1876, the temple towered over the area with its more than sixty-metre-tall tower. Nearby, on today’s Joannitów Street, you could find the Gustav Freytag Evangelical secondary school for boys designed by Richard Plüddemann and Karl Klimm in the early 20th century. Before the war, this entire area used to be called the Pond Fields, and up until 1945 it was an empty green area in the heart of the city. It was supposed to be turned into a city park, but these plans were abandoned when the focus turned to creating the large Południowy Park. The existence of the Pond Fields came to an end with the construction of the bus station, followed by the enormous Wroclavia shopping centre.

Gimnazjum św. Elżbiety; photo. from archives of Wratislaviae Amici polska-org.pl

Gimnazjum św. Elżbiety; photo. from archives of Wratislaviae Amici polska-org.pl

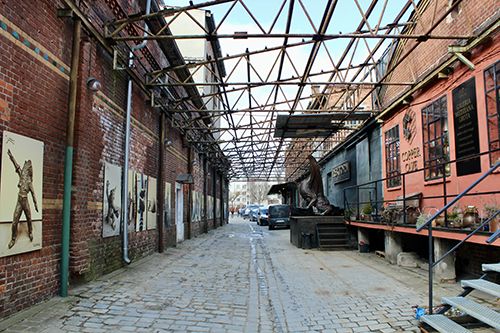

The brewery’s shaky fate

The proximity of the railway line enabled building quite a number of companies in the area, the largest of which was undoubtedly the brewery on Hubska Street. It was founded in 1894 by a restaurateur, who wanted to supply his Alter Weinstock restaurant with his own craft beer. Thirteen years later, the plant was bought from him by an association of innkeepers and tavern-keepers, who began brewing beer there to be sold in their establishments. Thus, more than a hundred years ago, local entrepreneurs challenged large brewing conglomerates such as Haase – one of the largest breweries in Germany located in today’s Krakowska Street. Destroyed during the war, the plant was rebuilt and started producing beers as Browar Mieszczański [Bourgeois Brewery] – eventually, it shut its doors in 1996. Since 2003 it has been privately owned and currently serves as a space for various cultural events.

Browar Mieszczański; photo. Wiktoria Mróz

Browar Mieszczański; photo. Wiktoria Mróz

Collected by: Szymon Maraszewski